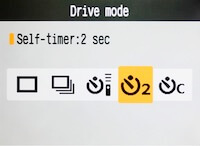

Step 6: Set your camera mode

There are three different techniques you could use to make your camera use a slow shutter speed, but we'd usually recommend option 2.

Option 1 - Shutter Priority

The most 'logical' approach is to turn your camera's mode dial to shutter priority ('S' mode for most cameras, 'Tv' for Canon). This setting allows you to directly dial in the shutter speed you want and the camera will automatically select the aperture value (f/#) which when used with your selected shutter speed in the current lighting conditions will result in a correctly-exposed photo (or, if you've set some exposure-compensation, then a photo with that requested exposure).

Flowing water starts to appear 'silky' if the shutter is open for at least about ¼ second. The longer (or slower) the shutter speed is, though, the silkier the flowing water will appear, so keep scrolling to even slower shutter speeds if you can. For the camera to check how much light is out there in your scene and decide if the selected shutter speed is allowable, you may need to half-press the shutter button briefly to 'wake the camera up'. Make sure to keep an eye on the automatically selected f/number when scrolling your shutter speeds though: If your f/# starts blinking at you (or flashing red, or giving some other warning) then you've scrolled your shutter speed too far (ie there's no f/# big enough, ie there's no aperture hole small-enough to prevent over-exposure with your selected shutter speed). If this happens, simply scroll your shutter speed back the other way a bit until the f/# stops blinking. It can be a bit of 'trial-and-error' feeling your way to the longest shutter speed you're 'allowed', but you'll get there.

You might find that as the morning brightens, a previously acceptable shutter speed could later result in a blinking f/#. If this happens, then you'll just have to dial back your shutter speed so it's a little faster.

TIP: Often cameras display only the fractional part of the shutter speed, so ¼ may display just as '4'. Whole seconds are usually denoted by a double quotation mark " so 4" would be four whole seconds.

Option 2 - Aperture Priority

The second method (faster and easier in our opinion) to achieving the longest shutter speed you can in a given scenario, is to actually select aperture priority on your mode dial ('A' mode for most brands, 'Av' for Canon) and scroll your f/# all the way up to the biggest f/# available (eg f/22 or more).

While it may sound odd to dial in an f/# rather than a shutter speed, remember that an f/# is actually the size of the aperture hole in the lens. A big f/# is a small aperture hole, which doesn't let in much light, so the camera will then select a long shutter speed to go with it. Don't worry - you don't actually need to get your head around this if you don't want to, but this means that rather than having to feel your way to the longest shutter speed that you're 'allowed' to use while watching for flashing f/# warnings etc (as you do using the above 'shutter speed' method), which the camera would then just pair with the largest f/# anyway, here you can just dial in the largest f/# right away, and irrespective of the lighting conditions, the camera will automatically use the longest possible shutter speed that will result in correct exposure (or whatever exposure you've set with Exposure Compensation). No more trail-and-error, no more flashing f/#s, and if the day brightens up, then the camera will automatically start using slightly faster shutter speeds for you. So easy!

Tip: If you're a little pedantic like us, then rather than using the absolute maximum f/# your lens can do, perhaps just dial the f/# back one value and use that instead. The highest f/# values can sometimes result in slightly less-sharpness in your image overall due to diffraction issues…

Option 3 - Manual Mode

You can, of course, use full-on ‘Manual (M) mode’ on your camera if you really want to, or if you need to due to a really dark ND filter which makes it hard for the camera to meter properly, however manual mode is usually unnecessary. It takes longer to set up, and even if you really know what you’re doing, it has disadvantages compared with Option 2. You’d still need to use trial-and-error to find the right value, it won’t compensate for you as lighting conditions change and it’s easy to stuff up!

You'll already have set a nice low ISO (ie ISO 100), so you'll now need to set the shutter speed AND the aperture f/# yourself. You may as well start with dialling in a really large f/# for the same reasons as in Option 2, and then you'll need to dial in the correct slow shutter speed to go with it. You'll likely have to watch the camera's light-meter / exposure indicator, and keep scrolling the shutter speed until you finally reach the one that the camera says will give you correct exposure +/- 0 (or whatever exposure you want). This would have been done for you in aperture priority mode.

If you're using Manual mode because you're using an ND filter that's so dark that the camera seems unable to measure the light properly (ie Option 1 or 2 is giving you weird results), then the technique here is to still use a large f/# and then just experiment with longer shutter speeds until you get a result you're happy with. If the photo is coming out too dark, then try a longer shutter speed next time, or a smaller f/# (or if you must, a larger ISO). If the photo's too bright, then use a faster shutter speed, or a larger f/# (or lower ISO). If you need to, you can even use shutter speeds longer than the camera's usual 30-second limit by using 'Bulb' mode along with a plug-in timer release.

If you're completely lost and have no idea what shutter speed to use for a super-dark ND filter, then you can actually calculate it: First take a correctly-exposed, slow shutter speed shot without the ND filter attached to your lens and note down the shutter speed you managed. Fixed ND filters all have a rating that describes how much light they let though. This rating is either written as an ND number (ie 'ND8' which lets 8x less light through, thus allowing a shutter speed that's 8 times longer) or alternatively an ND filter can be rated in terms of the number of 'stops' of light it cuts out (ie a '8-stop' ND filter). These are not the same thing. Each 'stop' of light reduction actually means halving the amount of light coming through. Two stops halves it twice, so that'd be 4x less light. Three stops is 8x, four stops is 16x, eight stops is 32x, etc.

| ND# |

Stops |

Shutter Multiplier |

| ND4 |

2-stops |

4 times longer |

| ND8 |

3-stops |

8 times longer |

| ND16 |

4-stops |

16 times longer |

| ND32 |

5-stops |

32 times longer |

| ND64 |

6-stops |

64 times longer |

ND128 |

8-stops |

128 times longer |

So using the above table, you should be able to work out how many times darker the world looks through your ND filter (ie a 2-stop filter is an ND4 which makes the world 4x darker) which tells you how many times longer your shutter speed can be (ie 4 times longer for an ND4) compared to your initial test photo. So if the perfect shutter speed without the ND4 filter was say 3" (3 seconds) then with it on, you would use 4 x 3" = 12" seconds (or the closest selectable value, possibly 10") and you'd end up with the same exposure.